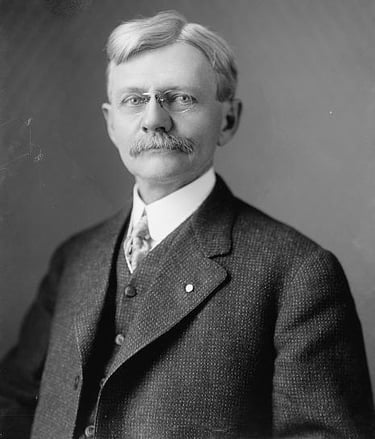

Lawyer, Governor, & Vice President

Thomas Riley Marshall

Thomas Marshall was born March 14, 1854, the only son of Dr. Daniel Marshall and his wife Martha (Patterson) Marshall. He was born in North Manchester, where his father kept a medical practice. Martha suffered from tuberculosis, and throughout his life Daniel sought ways of treating her. This led the family to traveling as Daniel searched for the right climate for his wife’s health – from Illinois, to Kansas and Missouri.

His father had an interest in politics, and considered himself a Loyalist Democrat. It was around this time that Abraham Lincoln and Steven A. Douglas were travelling around Illinois conducting a series of debates vying for the senate seat. Daniel took his young son, Thomas only being four years-old at this time, to one of these debates. During the debate, Lincoln took Thomas upon his knee while Douglas debated. Then, not to be outdone, Douglas did the same. It was afterward that Thomas said he liked the tall lean man, and it became a cherished memory Thomas kept.

Martha’s health had the family moving to Pierceton next. Thomas attended schools in Pierceton, Warsaw and Fort Wayne, but he sought greater opportunities. By the time he was 15 years-old, he was attending Wabash College. He graduated in 1873 with high honors and a bachelor of arts degree. Thomas earned his master’s in 1876.

Upon graduation, it was time to select a line of work, and Thomas had an interest in becoming a lawyer. To do this required on-the-job training through an established firm. He first began work with Hooper & Olds. Hooper was one of the first lawyers in Columbia City, and Olds was cousin to Thomas’ mother. He earned hands-on training for a time, and was admitted to the bar April 26, 1875. He was able to open his first law practice at the age of 21, right in the editorial room for the Post – Columbia City’s Democrat newspaper.

Just two years later Marshall had opened a law practice with William McNagny, and the two were later joined by Philemon Clugston. Each excelled in their own right with a different set of skills. Marshall set himself apart as a fantastic orator and storyteller. His humorous anecdotes and use of literary and Biblical quotations could reach the heart and mind of any juror. The skill of Marshall, McNagny and Clugston earned a high reputation for the law firm.

Marshall was a pillar of the Presbyterian Church in town, and was active in the Columbia City Presbyterian Sunday School and he taught a men’s Bible class. He continued to live with his parents in their home on West Jefferson Street. His mother was an active part of his life, but by 1894 both of his parents had passed.

Marshall, at 41 years-old, was appointed as a special judge for a case in Angola during the summer of 1895. It was here he was introduced to 23-year-old Lois Kimsey, who was working as a deputy for her father William E. Kimsey’s office, the county clerk. The two quickly became enamored with one another, and soon both Angola and Columbia City were anxiously anticipating the couple’s nuptials.

Marshall married Lois October 2, 1895. The two would remain devoted to each other throughout their lives. It was said that in their marriage the couple only spent two nights apart. Pretty and spirited, Lois became an active part of Columbia City society, and she played a part in encouraging Marshall to return to politics, which they were both actively involved in.

Marshall was picked for the Democratic nomination for governor for 1908, an election he ended up winning. Opposing him in the general election was Republican James E. Watson. Primary to this race was the discussion of prohibition. Marshall expressed support of prohibition, and it was the position of the Democratic party to allow it to remain in communities that supported it. It gained the support of several prohibitionists in the state and this, accompanied with tensions within the Republican party, led to Marshall’s victory. He was the first Democrat elected to the office in two decades.

Marshall was formally inaugurated on January 11, 1909 and remained in office until 1912. His focus in his term lay in reforms following the progressive agenda. This meant a focus in addressing problems found in monopoly, urbanization and fast-growing industrialization. His successes came in the passing of a child labor law and a law on corrupt election practices. Other laws he helped pass included an employers’ liability law, a pure food law, medical inspection of school children, a minimum wage for teachers and taxing on corporations. Marshall opposed capital punishment, and issued many pardons during his term.

Marshall is also credited with laying the last brick right at the start/finish line at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway, which he did December 17, 1909.

Indiana at the time only allowed a governor to serve one term, and Marshall had intended to return home to Columbia City, but fate had other ideas.

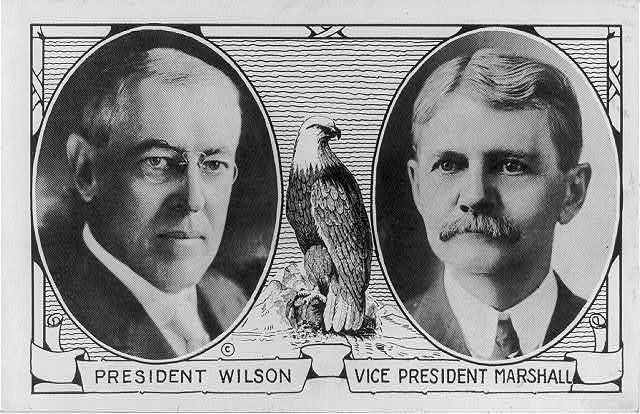

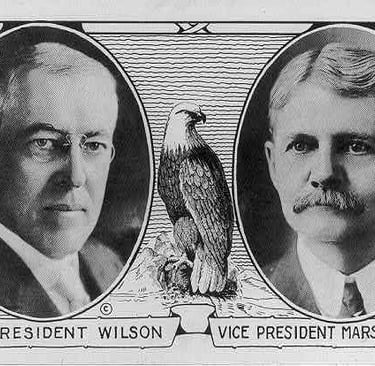

Woodrow Wilson had secured his nomination in the run for president, and was in need of a running mate. Indiana was a key part in getting the Midwest vote, and Marshall’s popularity made him the choice of the state’s delegates to run as Wilson’s vice president. The pair won the 1912 election, and the two were inaugurated on March 4, 1913. Marshall had become the fourth Hoosier vice president.

Marshall and Wilson were very much opposites – with Wilson having a much more serious demeanor to Marshall’s down-to-earth nature. Wilson would rarely consult Marshall on the issues faced during his presidency, and sometimes months would go by without correspondence between the two.

It made the role of vice-president a limiting one, and Marshall offered many quips to express his thoughts on the matter. He famously said, “I was the Wilson administration’s spare tire – to be used only in case of emergency.”

His other quips were, “I now have the best job I ever had – no responsibilities,” and “Vice presidents, like little children, should be seen but not heard.”

He would often make jokes about his office, once saying, “Once there were two brothers. One ran away to sea; the other was elected vice president. And nothing was ever heard of either of them again.”

Despite the limitations of his role, Marshall remained loyal to the Democratic party, and therefore to Wilson. His wit and willingness to find humor in things may have surprised many of the older leaders of Washington at first, but many grew to enjoy Marshall’s humorous anecdotes. Marshall’s main role was to preside over the Senate.

His office was very small - so small in fact the door was required to be left open to have the necessary cubic feet of air. Guests would frequent the building led by guides, who would stop and point at Marshall. Marshall used his humor to address these groups saying, “If you look on me as a wild animal, be kind enough to throw peanuts; but if you are really desirous of seeing me, come in and shake hands.”

It’s his humor that made him famous thanks to a one-liner that caught widespread attention. There’s been a few versions of the story told, but the general consensus begins with Senator J.L. Bristow, from Kansas, who was giving a lengthy speech where he expanded on the many things “this country needs.”

After the 10th or 11th time hearing the phrase, it was Marshall that uttered the phrase “What this country needs is a good five cent cigar.” This humorous quip was quickly spread about the room, and was picked up by the newspapers of the time. Soon after the vice president was showered gifts from cigar makers. Marshall later explained the quote was merely a figure of speech. That what he truly meant was what the country needed was for its people to get down to earth and buckle down to thrift and work.

When it came time for reelection, Wilson and Marshall were once again selected by the Democratic Convention in 1916. The two won the election in November with a narrow victory over Charles Evans Hughes and Charles Fairbanks (also from Indiana). With the win, Marshall became the first vice president in almost a century to be reelected to a second term.

While in office, there were many topics that needed to be addressed. Across the world, the Spanish flu was wiping out many of the populous. One of the main issues of the day was Prohibition, and the 18th amendment had been passed January 1919. It was later repealed in 1933 with the passing of the 21st amendment. On a personal level, Marshall was against the use of alcohol, but he also believed the choice should be made by the individual whether they should drink or not.

Another issue was women’s suffrage, which was passed by Congress on June 4, 1919. Marshall had opposed women’s suffrage though, having been quoted saying, “Women had a right to shave and sing bass if they wanted to, but that I was not going to assist in the process.” Marshall also supported the Democratic process though, and is pictured signing the suffrage bill after its adoption.

In the lead up to World War I, a group of senators opposing involvement would filibuster, the likes of which lasted weeks and sometimes even months. This prevented several bills Wilson supported to be passed. Marshall led the Senate to adopting a new rule allowing filibusters to be broken by a two-thirds vote, which was adopted March 8, 1917.

Marshall feared the enacting of the draft, but also supported Wilson’s efforts to build up the military before declaring war. The United States officially entered the war April 1917. Marshall was largely excluded from the war planning, but traveled across the country delivering speeches and encouraging Americans to purchase Liberty Bonds to support the war effort.

In their personal lives, Lois had become involved with different charity organizations in Washington. It was there she became acquainted with the Morrison family in 1917. The mother had seven children, and struggled in poverty to take care of them, one of whom was frequently ill. His name was Clarence Ignatius Morrison, and Lois became quite taken with him. It wasn’t long before Thomas had too. They named him Morrison, but called him “Iggie,” and he came to live with the Marshall’s where Lois could provide him with his own nurse. He seemed to flourish with the Marshall’s who had taken him in as their own son. Sadly, illness took Morrison when he was just three and a half years old. It was a devastating loss for Marshall. In his book, Marshall said, “I shall never see the glory of another and a fairer world, until I see his curly locks again and hear the music of his voice amid the angelic choir.”

The war was a stressful time for the country and its administration. Wilson made an address known as the Fourteen Points, in which he outlined long-term objectives regarding the war. One of these points was to establish a League of Nations, an international intergovernmental organization, whose mission would be to maintain world peace. Wilson left the country for Europe in early 1919 to negotiate a peace treaty (which became the Versailles Treaty signed in June 1919). In his absence,

Marshall presided over the cabinet. He did this for only a short time though, saying he felt the vice president could not keep a confidential relationship with the cabinet under the executive branch and the senate under the legislative. After Wilson had returned to the United States, he engaged in a speaking tour to promote his League of Nations plan. In September while in Colorado, Wilson suffered a stroke followed by a more severe stroke the next month. Wilson was rushed back to Washington and confined to his bed for many months.

The exact status of the president was kept secret from the nation. Very few people, including Mrs. Wilson and his doctors, saw Wilson in person. Marshall was kept completely in the dark, which was done because Wilson’s administration feared Marshall would attempt to enact the constitution, which declared a vice president could assume the duties of the president if the president were unable “to discharge the powers and duties of the said office.”

In fact, it was J. Fred Essary, a correspondent for the Baltimore Sun, who was tasked with informing the vice president of Wilson’s condition. It was a job given to him because it could not be considered a formal correspondence as it was outside the government. Marshall was told the president might die at any moment; news that left him completely silent. “It was the first great shock of my life,” Marshall later told Essary. Marshall was put into a difficult situation. Many put pressure on him to take over the presidential duties, while others argued it would appear as though Marshall were trying to usurp the office. He would go on to tell his secretary that had he acted as interim president, he could potentially throw the country into civil war. The challenge was that while the constitution had established a clause for transferring power, it did not state the process of how it should be done. It would only be legal if it could be signed by the president or by two-thirds vote Marshall had noted. Neither were possible, and Marshall said he would not do it, believing this was the right thing to do.

Marshall was tasked with hosting foreign dignitaries as part of his duties while Wilson was incapacitated. Among them were the king and queen of Belgium and Edward Prince of Wales. Wilson had begun to recover by 1919. Soon after the 1920 election was won by Republicans Warren G. Harding and Calvin Coolidge. Likely relieved for the change, Marshall telegraphed the incoming vice president, “Please accept my sincere sympathy.” Marshall left office in March 1921 and retired to Indianapolis. He was appointed by Harding to serve on the Federal Coal Commission and as presiding officer to the Lincoln Memorial Commission. He also wrote a syndicated newspaper column and wrote articles for many magazines. He was a frequent favorite for public speaking.

In May of 1925, Marshall had become quite ill with influenza. It didn’t stop him though from returning to Columbia City to deliver the commencement address at Columbia City High School. The next day he spoke at the North Manchester College commencement. Just three days later the Marshalls were called to Washington. Marshall was so weak though he was confined to his bed. Then on a Sunday morning, June 1, 1925, Marshall was reading the Bible to Lois when he passed away. He was 71 years-old. He was laid to rest in Crown Hill Cemetery in Indianapolis.

Regarding Thomas Marshall, Columbia City’s own Rob McNagny might have said it best: “He was common as an old shoe, in fact more comfortable to have around than most old shoes.”

Thomas Riley Marshall

Lois Kimsey Marshall

Thomas Marshall with "Iggie" Marshall

Woodrow Wilson and Thomas Marshall

Lois and Thomas Marshall

Thomas Marshall